Costume Designer Susannah Buxton has worked with Cosprop on many of her productions such as ‘The Woodlanders’, ‘Death Defying Acts’, ‘As You Like It’ (2006 version), ‘Tipping the Velvet’, ‘Fingersmith’, ‘Downton Abbey’ and ‘Poldark’. She has also been part of the John Bright Collection project as she kindly supported our curator Elizabeth Owen and John Bright in the process of choosing items for the website among the thousands stored in Cosprop’s museum room.

How did you get to know Cosprop and the Collection?

I took a one year postgraduate course in Radio Film & Television at Bristol University, then worked as a costume assistant at BBC Bristol and then for the BBC in London for a few months. I’d been to Cosprop with both of the designers that I worked with there. I didn’t know about the collection then, neither of the designers seemed to use it. I only learned about it when I started designing myself and John brought an original piece out from it to demonstrate a detail, in a fitting. It was exciting to know the collection existed. Many designers didn’t realise that they could access it, I think they might know now that the collection is digitalised.

What role do the John Bright Collection and other museum archives play in your design process?

I quite often start with the museum room because my design office is usually here at Cosprop. Looking at originals is the most important part of the preparation and there is never enough time to spend researching, once the actors are cast. The more research you are able to do, the more the production value of the drama benefits. I also go to the V&A and other museums, Worthing has a good collection. Looking at paintings of the period in books and galleries, particularly the National Portrait Gallery here in London is invaluable, and of course online too.

Unfortunately, the V&A has to restrict to two costumes that you choose online. I was lucky to have a contact when I went to the V&A to research 18th Century middle class dress for Poldark. Susan North was kind enough to find many examples for me, but its more often the upper class costume to have survived. In Worthing, I was able to study the collection and handle some of the clothes as long as I wore the white gloves, as their collection is less in demand. This was rather special, helping me to appreciate the atmosphere, shape and feel of a costume.

How do you feel when studying and handling original items?

It’s just thrilling to look at a piece of fabric, to be able to touch it and to know where it comes from and its date. It’s a connection to the past, a piece of history. All costume designers who work particularly in historical costume are interested in history… different periods in different countries. You couldn’t not be, could you? It would be an isolation, historical costume is so much about the politics and the manners of the time. Restrictions in clothing are often closely related to politics and can evolve into something like those extravagant white ruffs – the more extravagant, the richer the fabric, they would show your wealth, that was very important at most periods of history. The costume will tell you so much about the character.

Has your research process changed over the last few years since most international museums have started putting their costume collections online?

It is fantastic because you can see more costumes, but I would never just use that, I think the whole point of researching using originals is the tactile quality, to look at them and to be able to touch them and turn them inside out. It’s great to look at them online, but it’s not enough, I don’t think.

The process of creating a historical costume may start with a copy of the item. During all stages of making, fitting and using it on set, people will react to it from their different angles, resulting in changes to the costume- or changes in the performances. Could you tell us a bit about your experiences with this process?

I probably disagree because this one (pointing to a dress she designed for Jane Eyre based on this collection item: https://www.thejohnbrightcollection.co.uk/costume/dress-with-separate-sleeves/ ) is probably the closest I have been to a copy. That was very early days in my career as a designer and I had less confidence, I suppose. The idea of looking at originals is not to copy them, the intention is to create a character. For that actor in that drama, things will be different. You’re taking the inspiration and understanding – but it would not necessarily work to recreate a costume. Costume design is not about copying paintings or original costumes. The characters have a life of their own and are taking part in a story. The original may be beautiful but it may not suit the actress, in shape or colour. When I used the original as reference for Jane Eyre, I decided against the lace which, in this case, I found more distracting for Jane. Otherwise I have to say, it’s pretty close to the original in that instance.

And even here, you chose a different fabric in just one colour rather than a small floral pattern.

Yes, a warmer colour, which suited the girl better. There was a dress for Catherine Zeta Jones for Death Defying Acts and I looked at many originals from the 1920s. One of them had the most beautiful deep rose colour, and I used this as reference and we matched it in the dye room, the style of the dress wasn’t used at all. You can get inspiration from small things – a beautiful sleeve detail or a shape. For a suit for Michelle Dockery in Downton Abbey we looked at a 1920s hunting, shooting and fishing suit and changed the style of it completely, but there was a lovely pocket detail which I kept.

With ‘copy’ I chose the wrong word, but it has inspired important thoughts on Costume Design which is great – what I was aiming at was the working process and the influence of collaborators.

You could not do it without the collaboration of specialist skills. At the fittings the costumes come to life and all involved contribute, in one way or another. It’s interesting to hear other people’s opinions – the specialist skills involved are not often yours. It’s very rare for a costume designer to also be a corset maker, a milliner, a tailor. And here at Cosprop, John will often come in, particularly if there is some imbalance that seems impossible to solve… He will usually see immediately where the problem is and point you in the right direction, its sometimes difficult to stand back from ones own work, and really look at it.

Fittings always have a limited amount of time, there’s only so long the actor will be patient, they need to head off to rehearsals. In that small space of time, you might not be looking at the details that, say for example, the tailor would look at. Somebody who works with tailcoats all the time will have a better eye about their balance.

My best example is probably Jim Carter, who is a big bear of a man and was going to be this very upright butler in Downton Abbey. We made a tailcoat for him here and the tailor explained how much he could change Jim’s posture by the cut of the tailcoat and he altered and altered until Jim kind of grew into it. Jim said that the minute he put it on, he became the part. The tailor was helping with the sloping shoulders of the time. To me, it was a revelation really seeing ‘Carson’ emerge.

Yes, it is often forgotten how important this is for men’s costumes too – the ladies’ corsets and underpinnings are just more obvious.

Yes, but the silhouette for men is just as important, it’s your starting point and then you can maybe move away from the fashions of the time, or from the particular shape or colour that was loved then that is less acceptable to the modern eye.

I think, these can also start to look appealing when everything is right – as you get to understand the aesthetics of the time…

Even if you are not a historian you will know if something is not right, as it distracts the eye. The viewer should be engrossed in the story, the art and the drama of it, not necessarily the costumes. Unless it’s a show piece costume of course that is essential to the scene. Generally, we’re designing costumes for people, they should look like their own clothes, one of the hardest things, I think to achieve.

Learning and research are essential to everyone involved in the process. The costumiers will help with stock in the fittings. (Cosprop’s costumiers oversee everything concerning a production’s use of existing stock, they pull outfit options according to the designer’s general concept, drawing from their knowledge of the stock and of all types of clothing styles throughout costume history) It’s just as important as with new makes to keep on going until it works. And here the costumier offers advice and help. And the actors have their input of course, I would never make people wear clothes they feel uncomfortable in, it distracts the actors from the part they’re playing. If its explained that they’re going to have to leap high in the air, you obviously have to help that with considering the cut of the trousers. As a designer, it’s ultimately your decision but its always valuable to hear how the actor feels and respect their ideas.

The art of making a historical costume is one of collaboration with all the different skills involved. There can be as many as 5/6 skilled technicians brought into one fitting, and that’s not including the dyers and breaking down artists who work behind the scenes. The main people in a fitting will be the designer, the assistant and the costumier, but coming in can be the corset maker, the seamstress, the tailor and the milliner. All who are invaluable to the designer and are rarely given the accolade they deserve. It would be impossible for any designer to create the finished costume without them and I have always been grateful for the amazing work they have done for me during my career.

Which films have influenced you the most as a designer (particularly your approach to historical designs?)

One of the first ones is the production of Persuasion Alex Byrne designed. That to me was designed so differently than many costume dramas that had been shown before. Actors were involved in everyday activities, in costumes that looked like their own clothes. And then Jane Campion, ‘Portrait of a Lady, The Piano.. and John Bright’s Onegin. There is a moment when the characters are ice skating, perfectly re-creating a painting from the time. And, of course, the Merchant Ivory films. I was still a student then and they were very inspirational. The list would go on and on but those are the ones that came to my mind. The Piano is just… I love the style of it – and its darkness. I love Janet Patterson’s work and I felt like a school girl when I met her, I might as well have been meeting David Bowie, I was so excited. It’s a long time ago but I remember thinking ‘oh, wow, Janet Patterson!’

Were you ever surprised at the impact of a specific costume you designed?

The Harem dress from Downton surprises me as to be endlessly asked for for exhibitions, it has never stopped touring. I suppose because it’s had its impact in the scene. In those days it would have been quite shocking. And then, there are two costumes that come into my mind: one because the audience laughed so much, it was Johnny Vegas in Tipping the Velvet as a ventriloquist. We made his suit and that of the dummy of the same tweed and also covered his suitcase in it. When he walked onto the stage the audience of supporting artists just roared – that was great. And then, one of my favourite costumes was Sally Hawkins, we made an Edwardian style ‘bee’ costume for her, for a fancy dress scene and it worked so well. They are others, but those came into my mind.

Do you have a favourite item in the John Bright Collection and if so, what fascinates you about it?

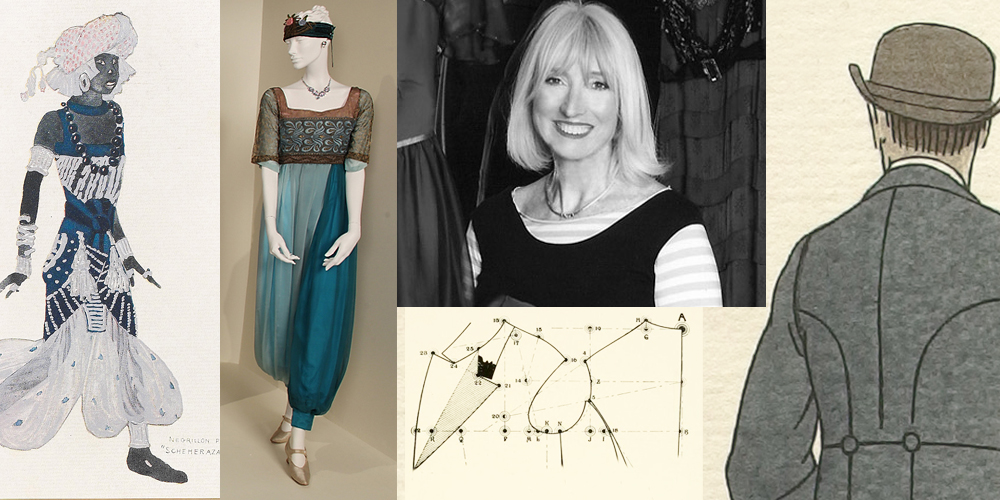

I think when we were looking through the boxes (to choose for the collection website), what astonished me were the costumes from the Ballets Russes. It was just ‘Oh my god, it’s the Ballets Russes!’ They are gorgeous. (https://www.thejohnbrightcollection.co.uk/group/ballets-russes/ more will be uploaded in this section soon). And then there is a waistcoat that was made from a gentleman’s grandmothers wedding dress. That little waistcoat! The fabric was 70 years old or so before he even decided to use it, such a lovely story from the past. (https://www.thejohnbrightcollection.co.uk/costume/wedding-waistcoat/ )

Can you remember a first encounter with an object that triggered a fascination with cultural history?

Funnily enough I’ve often wondered about this, the first encounter. When I was about ten I copied a portrait of Elizabeth I, the Armada Portrait, the only thing I remember about it is painstakingly drawing in all the pearls and colouring into it, I must have drawn it from scratch. Why did I do that? I didn’t originally study costume, I studied graphic design and illustration before working behind the scenes at the theatre, before going freelance at the BBC. It’s a very striking dress but why, when I was at primary school, it interested me, I don’t know. It would have been from a history book that my parents had. I have always liked drawing and ‘colouring in’ It is one of the things I did for pleasure.

And it’s great when one gets to understand later on that all those gems and pearls were genuine and what they would have cost at the time.

Yes, it’s a phenomenal costume. But when you’re ten… there was some kind of interest that came from somewhere. With my mother and my two sisters, we made all our clothes, it was that era, Vogue patterns and sewing machines – she sewed, we learned. It took a long time before I became a costume designer. There is so much you have learned at art school and you only gradually appreciate its value, and look back and see the influence that knowledge has had on your work, as John says “the difference between looking and seeing” is so important.

Do you collect anything yourself?

I don’t really, no, I did for a while, but I couldn’t store things. What I probably collect are fabrics. So, if there’s some leftover from a production and it is too beautiful it just ends up being at home. Or sometimes when I see beautiful pieces I can’t resist buying them. I bought a good length of lamé from a dealer…Italian…and it has even got a maker’s name with it. I don’t think it’s ever been used. You can’t get anything that looks quite so beautiful now. It’s got a process of making for that particular type of gold lamé from the 1930s, that is no longer used.

Sometimes I think, that’s the only ‘problem’ with looking at the collection items – when you see original fabrics and have to use something else, it can feel like losing that quality.

You are! The 1920s produced the most beautiful fabric designs but they’re very hard to recreate and there’s no way you can buy them anywhere. And that’s disappointing, when you’re designing for the 1920s, because they’re powerful, such strong prints. Unfortunately, there has to be a really good budget to be able to reproduce them and its virtually impossible to find a piece of fabric that comes anywhere close to those 1920s prints. All the fabrics get harder to acquire.

There were silks from India that were so good to use in period costume because they were copying their old designs, but that has mostly gone because now synthetic fibres are more commonly used to make them machine washable. Although digital printing is getting better and better. We can make copies of beautiful old prints and the seamstresses work into them to give then some depth, we are still restricted to fabrics with special coating, so it’s expensive and the quality of the fabric can change significantly. Still it’s early days with that technology but already we can recreate such lovely patterns. Old lace, which is increasingly difficult to source is reproduced digitally in some cases and worked into manually to give it depth by skilled seamstresses. This is a perfect example of contemporary technology relying on specialist practitioners. The film, television, theatre and opera industries that are invaluable to the UK could not survive without the skills of the milliners, seamstresses, costumiers and tailors who work alongside the designers, in creating these amazing productions for which we are world famous.